Seats-Of-Ease

(Click on any of the pictures in the article to enlarge.)

Seats-of-Ease

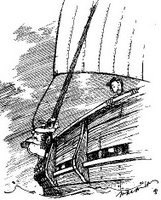

“If you want to relieve yourself . . . you have to hang out over the sea like a cat-burglar clinging to a wall. You have to placate the sun and its twelve signs, the moon and the other planets, commend yourself to all of them, and take a firm grip of the wooden horse’s mane; for if you let go, he will throw you and you will never ride him again. The perilous perch and the splashing of the sea are both discouraging to your purpose, and your only hope is to dose yourself with purgatives.”

Eugenio de Salazar, 1573

This tongue-in-cheek passage vividly describes what it was like for one passenger to relieve himself (go to the bathroom) on a Spanish sailing ship during a sixteenth-century trans-Atlantic voyage. Obviously, this man felt the need to humorously describe what was otherwise considered a basic bodily function that was not frequently written about then—or today, for that matter. It’s a good thing he did feel like writing about it, because it is one of only a very few firsthand descriptions from that or any other period of what going to the bathroom was like on historic sailing ships.

This tongue-in-cheek passage vividly describes what it was like for one passenger to relieve himself (go to the bathroom) on a Spanish sailing ship during a sixteenth-century trans-Atlantic voyage. Obviously, this man felt the need to humorously describe what was otherwise considered a basic bodily function that was not frequently written about then—or today, for that matter. It’s a good thing he did feel like writing about it, because it is one of only a very few firsthand descriptions from that or any other period of what going to the bathroom was like on historic sailing ships.Have you ever been on a boat or a ship? Have you ever had to relieve yourself on a boat or ship? If you have, you probably never thought much about it; certainly, you didn’t consider writing about the experience, did you? Have you ever thought about relieving yourself on old sailing ships without flush toilets, where the human waste went, or what it was like to sail and live on board sailing ships for months or years at a time? Did you ever ask yourself what the living conditions on historic sailing vessels were like and how problems with the removal of human wastes (urine, feces, vomit, etc.) may have affected those conditions? All of these are important questions for people who study the history of sailing ships and are concerned about the conditions aboard them and the corresponding health of their crews. And you better believe that the engineers who designed the Space Shuttle or International Space Station had to think about such things.

By appreciating the realities of the effective removal (and, today, treatment) of human wastes from areas where we live, we can better understand what living aboard historic sailing ships may have been like. Conversely, we can begin to understand how the accumulation of these wastes led inescapably to very poor sanitary conditions in enclosed, damp, dark, and often crowded quarters and how these conditions were extremely unhealthy, even deadly in some situations.

Conditions aboard sailing ships

Because of their very nature, waterborne craft have usually been able to accommodate the “human need.” By simply eliminating human wastes directly into the sea or by throwing collected materials overboard, shipboard occupants established an efficient, common-sense disposal scheme.

Because of their very nature, waterborne craft have usually been able to accommodate the “human need.” By simply eliminating human wastes directly into the sea or by throwing collected materials overboard, shipboard occupants established an efficient, common-sense disposal scheme. In what were usually relatively small, undecked, or partly decked vessels limited to seacoasts, lakes, or rivers that made no voyages longer than one or two days without landing, there was no need for anything more elaborate than waste buckets or a small platform from which to answer the call of nature. Prior to the fifteenth century, when multiple decks became common in moderate and large vessels, such rudimentary methods of waste removal were undoubtedly in use on most vessels and, as situations warranted, they certainly persisted until the end of the age of sail (around AD 1850).

During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, as compasses and nautical charts were developed and watercraft that could withstand the rigors of sustained and repeated deepwater navigation were evolving, unique sanitary and hygienic problems began to appear. As vessels began to be decked over, which improved their seaworthiness and offered more protection from the elements, several factors combined to compromise these benefits: diminished air flow to spaces between and below decks, decreased light at lower deck levels, and accordingly, higher humidity below decks.

Of overriding importance is the fact that the “stacking up” of living surfaces (decks), one above another, created a birdcage-like environment in which every imaginable bit of debris, filth, and human waste from the decks above gravitated to the bilges below. The consequent accumulation constituted a rich organic compost in the lowest, foulest reaches of the ships.

As a direct consequence of the horrible conditions between and below decks, great numbers of vermin were able to breed and multiply virtually unchecked. Rats, lice, weevils, fleas, and cockroaches, to name a few, abounded.

Development of external sanitary facilities, improving conditions by trial-and-error

Conscious attempts to improve the unhealthy interior conditions resulted in the development of external waste-disposal accommodations. Any amount of human wastes eliminated directly into the sea, rather than to the interior of the hull, was advantageous, at least in terms of sight and smell, even if the connection between filth and disease that we appreciate today was not then understood.

Conscious attempts to improve the unhealthy interior conditions resulted in the development of external waste-disposal accommodations. Any amount of human wastes eliminated directly into the sea, rather than to the interior of the hull, was advantageous, at least in terms of sight and smell, even if the connection between filth and disease that we appreciate today was not then understood.The development of external sanitary conveniences was expedited by specific changes in northern European hull construction that occurred in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries. By the last quarter of the seventeenth century, these features were fully developed and most of them were retained with little or no modification until the early nineteenth century.

Basically, external sanitary facilities were made possible by the construction of platforms at bow and stern that consisted of overhangs and projections, on which devices were erected that emptied directly into the sea. Projecting shelves and chain wales (supports for mast rigging) on ships’ sides provided other structures upon which accommodations were fitted.

The Bow

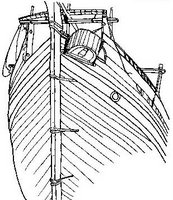

Evidence of hygienic conveniences in the projecting bow structures (beakheads, or “heads”—the origin of the common name of ships’ toilets) of ships of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries is sketchy. Wooden gratings, slots in the flooring, rails of the beakhead, and simple, holed boards as seats have all been suggested as having served a hygienic, waste-disposal function during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Evidence of hygienic conveniences in the projecting bow structures (beakheads, or “heads”—the origin of the common name of ships’ toilets) of ships of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries is sketchy. Wooden gratings, slots in the flooring, rails of the beakhead, and simple, holed boards as seats have all been suggested as having served a hygienic, waste-disposal function during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.The seventeenth century witnessed four important hygienic developments in the heads: the advent of seats-of-ease, fore turrets, roundhouses, and pissdales. Between 1670 and 1680, distinct individual sanitary accommodations, or seats-of-ease, placed within the structure of the head and equipped with trunking, or drainage sluices, made their first appearance on models, although we have archaeological evidence from the Wasa of 1628. Fore turrets, devices seemingly unique to the French, debuted and quickly disappeared, although they may have left an enduring legacy. In combination with the imitation of semicircular balconies, fore turrets may have helped bring about the appearance of roundhouses. These were “perhaps the most satisfactory form of convenience found in ships. Access was through a door in the [beakhead] bulkhead, there was often a small port for ventilation and light, and presumably the occupant was left in a solitary state” (J. Munday 1978, p. 127). The same cannot be said of another seventeenth-century development, the pissdale. This was a convenience installed at the head and amidships that consisted of a simple urinal trough plumbed with lead pipes extending directly through the platform of the head or through the sides of the ship. It was designed for, and experienced, heavy traffic, without regard for solitude or protection from the elements.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, an increase in the relative area of the head platform allowed for more gratings, a greater number of freestanding necessary seats, and the arrangement of grouped, multihole conveniences placed against the forward-most part of the hull. About the middle of the nineteenth century, radical changes in bow designs were brought about by the introduction of iron-hulled ships. These changes so affected the sanitary accommodations at the bow that they were necessarily moved amidships.

Of all the types of hygienic conveniences developed at the bow over the course of some five hundred years, only the roundhouse survived into the twentieth century, and that in a modified form.

Amidships

Steep- or necessary tubs seem to have been moved from the sterns and quarters to the main chains of either or both sides of the hull about 1550. Early in the seventeenth century, they are seen in association with angular side-shelves, but necessary tubs are not represented in the pictorial record after this brief appearance. Side-shelves, whose development may have resulted form the shift of garderobes from the quarters to the main chains, were depicted throughout the seventeenth century and became rare in the art of the 1700s. Multihole platforms were prominent from the mid-nineteenth century, after the removal of the “heads” to positions amidships.

The use of pissdales continued unabated from their initial appearance in the last half of the seventeenth century until the end of the nineteenth. Indeed, until the mid-twentieth century they saw service as crew’s urinals placed amidships and plumbed directly into the sea.

The Stern

The employment of three primary external hygienic accommodations located in the sterns of fifteenth-century ships has been suggested: 1) barrel-like attachments on the stern quarter (sides of the stern) and over the transom and counter (squared-off stern end and slight undercut, respectively); 2) closet-like additions over the counters that projected from the sterncastle, similar to garderobes in contemporaneous castle architecture; and 3) structures that closely resembled castle turrets and probably performed much the same function.

In the course of the sixteenth century, steep-tubs were moved to the main chains and garderobes to the quarters, where the walls of the sterncastle were still relatively flat. However, garderobes disappear from the pictorial record after about 1525 and are not seen again until the early seventeenth century, by which time they had been moved to the fore end of the open quarter galleries. Quarter galleries remained largely open through the remainder of the 1500s, but the first third of the seventeenth century witnessed their increasing enclosure, a development that may have gained some impetus from the placement of the garderobe there. The remainder of the 1600s was a period of grand-scale decorative elaboration, readily apparent on the quarter galleries of ships of the time.

Throughout the eighteenth and most of the nineteenth centuries, hygienic accommodations at the stern remained virtually unchanged. Quarter galleries with one, two, and occasionally three levels remained the principal conveniences for senior officers. But by the fourth quarter of the nineteenth century, quarter galleries had been eliminated because of major structural changes necessitated by the advent of iron-hulled ships.

It appears that early flushing water closets were first installed in the quarter galleries of British naval vessels in 1779. However, they do not seem to have been used extensively until well into the 1800s.

Biographical Statement

Dr. Joe J. Simmons III is a dentist currently living in New Mexico. He has come full circle back to his archaeological roots. He began his archaeological career in the Southwest, pursued underwater archaeological research interests in the Caribbean for nearly 20 years, then became a dentist and settled in the Southwest; he is now literally surrounded by prehistoric archaeology sites. His interests include diving, sailing, photography, hiking, and, not surprisingly, archaeology.

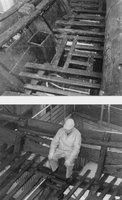

In 1628, the Swedish warship Vasa (or Wasa) sank suddenly in Stockholm harbor. She was located and successfully recovered in the late 1960s/early 1970s; conservation (stabilization) of the magnificently preserved wood took more than 20 years to accomplish. The wooden timbers of the ship and numerous other organic artifacts were well preserved due to the cold temperatures and low oxygen content of the waters at the bottom of Stockholm harbor. Two beautiful examples of nearly complete free-standing seats-of-ease were

In 1628, the Swedish warship Vasa (or Wasa) sank suddenly in Stockholm harbor. She was located and successfully recovered in the late 1960s/early 1970s; conservation (stabilization) of the magnificently preserved wood took more than 20 years to accomplish. The wooden timbers of the ship and numerous other organic artifacts were well preserved due to the cold temperatures and low oxygen content of the waters at the bottom of Stockholm harbor. Two beautiful examples of nearly complete free-standing seats-of-ease were  discovered in the beakhead of the Wasa. A Wasa Museum employee demonstrates the correct orientation of the user on these early seventeenth-century hygienic accommodations; they were simple, but quite effective, devices.

discovered in the beakhead of the Wasa. A Wasa Museum employee demonstrates the correct orientation of the user on these early seventeenth-century hygienic accommodations; they were simple, but quite effective, devices.Illustrations.

1. Hanging Out (Simmons, 1997), p. 74

2. Navire Royal 1626 (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), p. 48

3. WA’s Kraeck (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford), p.18

4. Arab dhow, sanitary boxes (Howarth 1977), p. 21, 22

5 and 6. Wasa’s beakhead seats-of-ease (G. Ilonen 1998), p. 45, 46.

San Juan Sailing Club

San Juan Sailing Club

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home